Sequencing our 3.2 billion DNA base pairs is becoming increasingly crucial as genomic testing gains widespread acceptance.

AI and Genomics – How AI will be overpowering the future DNA.

Advancements in genomics are improving the detection of mutations that can lead to illnesses, with the potential to revolutionize personalized medicine by enabling the development of more effective treatments for genetic disorders.

- High-performance computing is revolutionizing the field of genomics by accelerating the speed of analysis and processing of large-scale gene sequencing data sets.

- However, genomics is facing a massive Big Data problem. Scientists are struggling to process a growing volume of data as precision medicine turns to gene sequencing for individual patients.

- By leveraging the computing power of graphics processing units, geneticists can speed up analysis and reduce the cost of processing the huge amounts of data produced by gene sequencing.

- in recent months, before attention shifted to the pressing issue of tackling the COVID-19 pandemic, artificial intelligence (AI) had been hitting the headlines in medical news. Most weeks saw the release of high-profile publications and announcements of how AI is forging advances in research or how it will transform healthcare. Genomics is one of the fields where expectations for AI are high. Our new report Artificial intelligence for genomic medicine looks beyond the hyperbole into how AI is currently being used, where things might be heading, and the challenges ahead.

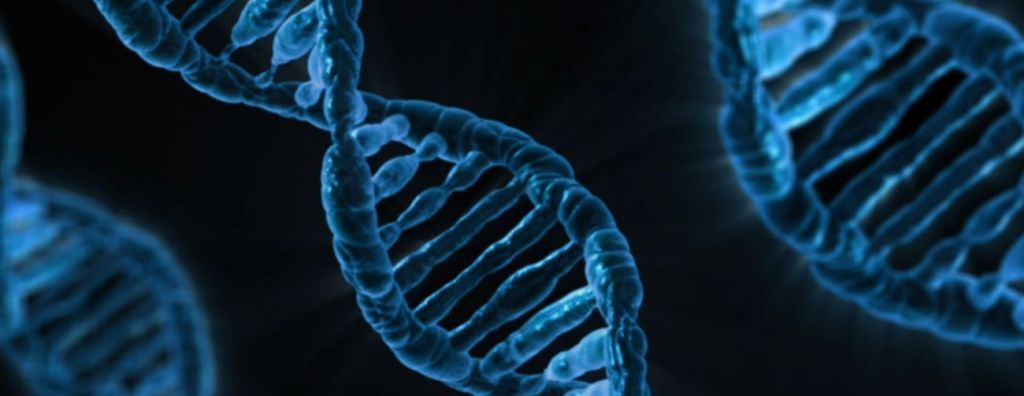

What is a Genome?

A genome is an organism’s complete set of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), a chemical compound that contains the genetic instructions needed to develop and direct the activities of every organism. The DNA molecules are made of two strands and each strand is made of four chemical units. The bases are adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G) and cytosine (C). Bases on opposite strands pair specifically; an A always pairs with a T, and a C always with a G.

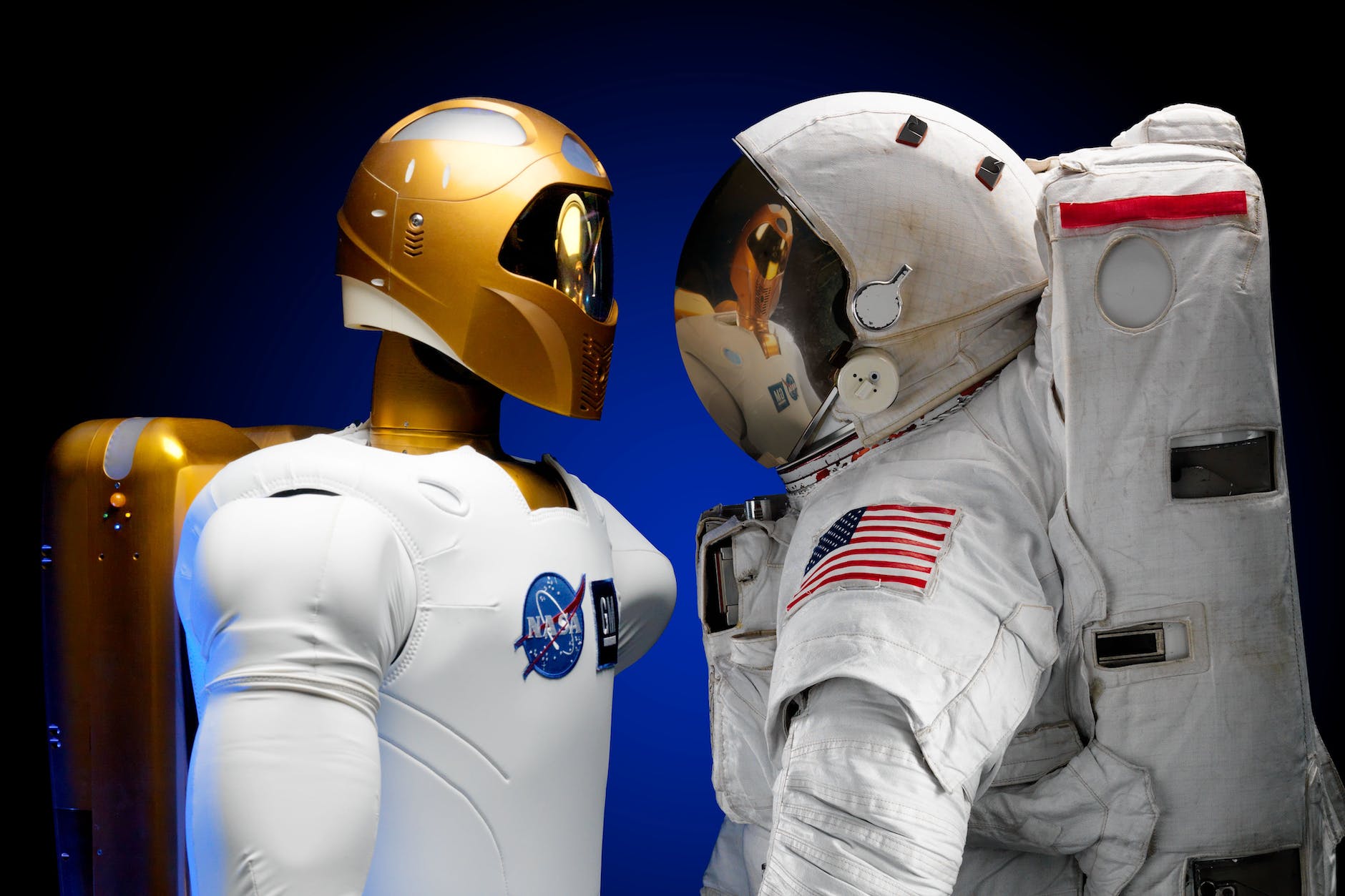

What is Artificial Intelligence?

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the ability of a digital computer or computer-controlled robot to perform tasks which are normally associated with human beings. AI is a science and a set of computational technologies that are inspired by but typically operate quite differently from the ways people use their senses to learn, reason, and take decisions and actions. AI can be created as software or tools. They are capable of imitating human intelligence in certain instances and sometimes they can even exceed human potential.

What sequencing technology is used in the human genome project?

Sequencing refers to determining the exact order of the base pairs in a segment of DNA. The primary method used by the Human Genome Project (HGP) to produce the finished version of the human genetic code was map-based, or bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) based sequencing. Human DNA is disintegrated into pieces that are manageable in size. The fragments are then cloned in bacteria, which store and replicate the human DNA so that it can be prepared in quantities large enough for sequencing.

Examples of Genomics AI Companies

1. Microsoft

2. Illumina

3. Lucigen

4. Molecular Assemblies

5. Sema4

6. WuXi App Tech

7. PerkinElmer

Are Genomics and AI a good match?

In the field of Genomics, the expectations for Artificial Intelligence are very high. It is assumed that in Genomic medicine and research, AI, machine learning and deep learning are in ascendancy. Some examples of AI applications in the genomics space include drug discovery, gene editing, and variant analysis. There are also a growing number of academic machine-learning resources for genomics, some of which have already been routinely used in clinical genomics analysis for some time. So, this is evidence of how great genomics and AI work effectively together and are thus a good match. Coupled with more powerful computing infrastructure, machine learning and deep learning are presenting diverse opportunities. By facilitating the analysis of large and complex research datasets, machine learning will accelerate new discoveries in genomic medicine: current studies are seeking to understand how cancers evolve, examine microbiomes, and analyze multi-omics datasets. The need to facilitate the safe and effective deployment of AI for genomic medicine, and other areas of healthcare. Failure to act promptly would risk:

1. Compounding existing disparities. As AI is applied more routinely to genomic datasets, some pre-existing challenges will be further deepened, notably the lack of diversity in genomic datasets and databases. An imbalance of information on some populations can lead to misdiagnosis, as well as uneven success rates in personalized medicine and clinical trial outcomes. If left unresolved, the development of AI algorithms using unrepresentative genomic datasets will perpetuate and further entrench health disparities for underserved groups.

2. Opportunity costs. A significant amount of investment is being poured into growing AI for healthcare. To make the most of this investment, it is crucial for AI to be channelled effectively to address the most pressing problems together with those where AI is most likely to add value. This requires close collaboration between AI practitioners and genomics domain experts to identify the most appropriate questions to address, determine which machine learning approaches to apply, and recognise limitations in datasets, methods, and current knowledge so as to avoid AI models that may lead to misleading insights or faulty predictions.

3. Over-reliance on technology to solve complex problems. Despite its vast potential, AI alone will not advance genomic medicine and it certainly cannot do so without the necessary oversight, safeguards, validation, robust ethical appraisals, and public engagement. The temptation for ‘tech solutionism’ has come into sharp focus during the current pandemic, and recent reports and commentaries have warned against the rushed deployment of AI and digital technologies without credible supporting evidence and careful oversight.

Examples of technologies (AI) that are transforming the medical field include: high-throughput genome sequencing, CRISPR, and single-cell genomics.

How AI & ML are used in Genomics

Even though using AI tools in genomics is still in its prime stages, researchers have benefitted immensely from developing programs that are able to assist it in specific ways. Examples of this include the following:

1. Examining people’s faces with facial analysis AI programs to accurately identify genetic disorders.

2. Using machine learning techniques to identify the primary kind of cancer from a liquid biopsy.

3. Predict how a certain kind of cancer will progress in a patient.

4. Identifying disease-causing genomic variants compared to benign variants using machine learning.

5. Using deep learning to improve the function of gene editing tools such as Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR). CRISPR provides the power to edit. E.g. Correct typos, or “mutations,” that can arise in genomes — and do so with an unprecedented level of precision.

The Importance of AI in Genomics

- There remains an increase in complexity and the number of DNA sequencing techniques and as such, there is a need for Artificial Intelligence or Machine Learning in Genomics. Genomics researchers rely on AI computational tools that are robust enough to manage and interpret any valuable information that might be hidden in any large dataset.

- DNA sequencing and other biological techniques will continue to increase the number and complexity of such data sets. This is why genomics researchers need AI/ML-based computational tools that can handle, extract and interpret the valuable information hidden within this large trove of data.

1. The genomics field continues to expand the use of computational methods such as artificial intelligence. In doing so, it helps to improve our understanding of hidden patterns in large and complex genomics data sets from basic and clinical research projects.

2. AI, specifically, Machine learning analysis is beneficial for disease research and genomic tools like CRISPR.

3. National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) is identifying and shaping its unique role in the convergence of genomic and machine learning research.

The promise of AI for genomic medicine

The AI approach – machine learning – and its subset, deep learning, are on the rise in genomic medicine and research. Ten years ago, there were roughly 300 publications listed on PubMed relating to AI in genetics or genomics, rising to around 2,000 in 2019. Publications aside, there is a growing range of companies building AI applications in the genomics space, for example, drug discovery, gene editing, and variant analysis. There are also a growing number of academic machine-learning resources for genomics, some of which have already been routinely used in clinical genomics analysis for some time.

This rise of AI in genomics is unsurprising. Genomics – a ‘big data’ field – requires computational approaches to interrogate the enormous volume of data generated by sequencing technologies and to marry it in meaningful ways with other biological and clinical data. Analysing these datasets for new biological insights can be especially difficult when the rules have to be explicitly predefined, step by step, within the computer code. Instead, machine learning techniques can learn from data without the need to specify explicit rules.

Hope, hype and hitches

Coupled with more powerful computing infrastructure, machine learning and deep learning are presenting opportunities to:

Generate new insights from large-scale datasets – improving our understanding of genomic variation in relation to health and disease

Better streamline key analytical problems in genomics analysis – helping focus the search for disease-causing variants and reducing clinical analysis times

Nearly every stage of the genomics data pipeline is affected by developments in AI, though the greatest activity is in the research phase. By facilitating the analysis of large and complex research datasets, machine learning will accelerate new discoveries in genomic medicine: current studies are seeking to understand how cancers evolve, examine microbiomes, and analyse multi-omics datasets.

While we shouldn’t underestimate the eventual medical impact of this research, to date AI’s outcomes for genomic medicine – in a clinical context – are not commensurate with the hype that has surrounded it. Broadly, this is because the thresholds for adopting new technologies in healthcare are higher than for other sectors, given the potential for harm to patients that could arise from the misuse of an algorithm. More specifically, there is a range of issues which impede the development of robust, safe, clinically validated algorithms which are demonstrably beneficial. These issues – which include reproducibility, data silos, inadequate computing infrastructure, bias in datasets, privacy and security, lack of transparency, and regulatory ambiguity – will need to be addressed effectively if we are to reap the benefits of AI for genomic medicine.

An urgent agenda

Our report sets out seven priority policy actions that could go some way towards meeting the challenges in making AI work to the best effect for genomic medicine. Whilst there are currently more immediate urgent issues in health that will rightly take precedence, this does not absolve policy-makers and other stakeholders of the need to facilitate the safe and effective deployment of AI for genomic medicine and other areas of healthcare. Failure to act promptly would risk:

Compounding existing disparities. As AI is applied more routinely to genomic datasets, some pre-existing challenges will be further deepened, notably the lack of diversity in genomic datasets and databases. An imbalance of information on some populations can lead to misdiagnosis, as well as uneven success rates in personalised medicine and clinical trial outcomes. If left unresolved, the development of AI algorithms using unrepresentative genomic datasets will perpetuate and further entrench health disparities for underserved groups.

Opportunity costs. A significant amount of investment is being poured into growing AI for healthcare. To make the most of this investment, it is crucial for AI to be channelled effectively to address the most pressing problems together with those where AI is most likely to add value. This requires close collaboration between AI practitioners and genomics domain experts to identify the most appropriate questions to address, determine which machine learning approaches to apply, and recognise limitations in datasets, methods, and current knowledge so as to avoid AI models that may lead to misleading insights or faulty predictions.

Over-reliance on technology to solve complex problems. Despite its vast potential, AI alone will not advance genomic medicine and it certainly cannot do so without the necessary oversight, safeguards, validation, robust ethical appraisals, and public engagement. The temptation for ’tech solutionism has come into sharp focus during the current pandemic, and recent reports and commentaries have warned against the rushed deployment of AI and digital technologies without credible supporting evidence and careful oversight.

Efforts to explore the current pandemic using AI are already underway – there are already over 100 pre-print publications (preliminary reports that have not yet been peer-reviewed) that deploy machine learning for the study of the virus causing COVID-19. Many of these studies combine sequence data and machine learning, for example, to examine the virus’ evolutionary origins; to design antibodies; or to examine the host cellular response. So, while other health-related AI news may be scarce currently, the technology certainly hasn’t gone away. Nor should standards, safeguards, and the necessary scrutiny surrounding its development and deployment.

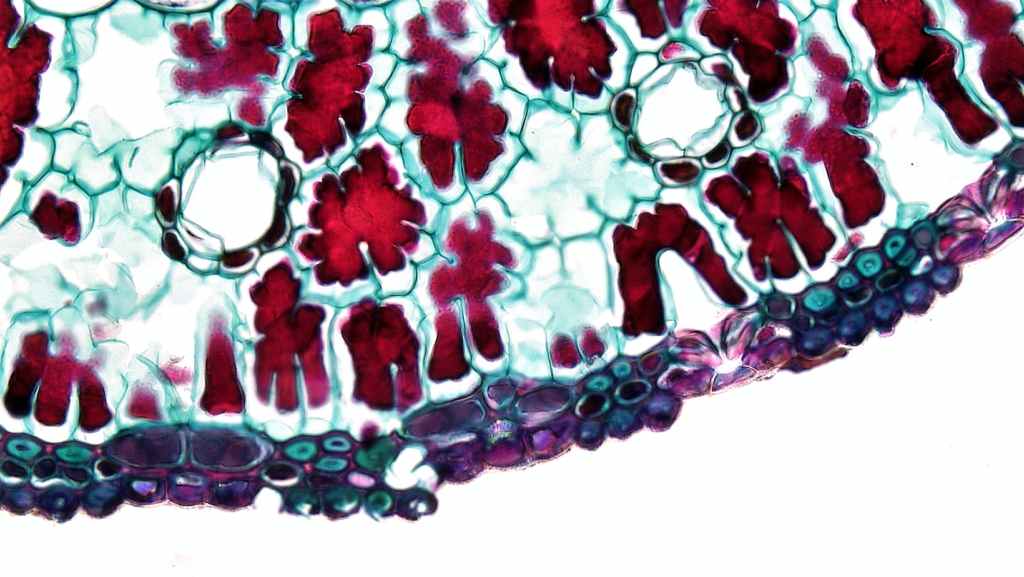

EXAMPLES OF ML APPLICATION IN FUNCTIONAL GENOMICS STUDIES USING DISEASE-APPLICABLE TISSUES

Functional genomic data have been used to advance the precision medicine of cancer. Recent progress has been made in utilizing functional genomics to inform precision medicine of common noncancer diseases including kidney disease. The following examples illustrate how functional genomics data obtained from disease-applicable tissues can be analyzed with ML in addition to other statistical methods to work toward the development of precision medicine for common noncancer diseases. Reeve et al. collected 1,208 kidney transplant biopsies to assess rejection-related disease by using archetypal analysis of mRNA phenotypes combined with principal component analysis (PCA), a dimensionality reduction method. Archetypal analysis is a type of unsupervised learning that identifies extreme or pure phenotypes within a training set. They calculated bootstrap corrected C-statistics, which are analogous to AUCs, and found that their archetypal analysis scores (C-statistics 0.73) were more predictive of allograft loss than histological diagnosis using the Banff classification (C-statistics 0.60) (P = 3 × 10−6).

In another study, Liu et al. examined cell type-specific differential mRNA expression in glomeruli isolated from IgA nephropathy patients. They used “in silico nano dissection,” an ML algorithm that predicts cell type-specific transcripts based on large data sets, to identify mesangial and podocyte cell-specific genes that were differentially expressed between IgA nephropathy and healthy control patients. They concluded that the mesangial cell genes were highly correlated to serum creatinine (P = 0.024) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (P = 0.025) progression for up to 4 yr following biopsy. Mass spectrometry was used to examine differentially expressed pathways in these samples as well as human mesangial cells that were incubated with serum from IgA nephropathy patients. They found several inflammatory pathways that were differentially expressed both in vivo and in vitro, along with pathways related to inducible nitric oxide synthase and endothelial nitric oxide synthase.

Leave a comment